Introduction

In the past few months I’ve come across several video advertisements on Youtube that are obvious deepfakes (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deepfake) . Seeing these, my curiosity was piqued, and I wanted to examine these videos closer. There has been a history of advertisement on the internet being used as a vector for social engineering (https://www.bitdefender.com/en-us/blog/hotforsecurity/facebook-ad-scam-tricks-investors-with-fake-messages-and-malware-disguised-as-verified-facebook-app, https://consumer.ftc.gov/consumer-alerts/2023/04/ads-fake-ai-and-other-software-spread-malicious-software, https://finance.yahoo.com/news/hackers-exploit-ad-tools-track-184948118.html), but in this case the video advertisements have the hallmarks of a social engineering attack.

Advertising and Social Engineering have many commonalities in their approach and we’ll discuss methods and appeals later, but the main difference between legitimate advertising sales and a social engineering attack (a scam or con), however, are that sales represent a tangible exchange with transparent intent, whereas a con does not. A salesman that legitimately pairs the concerns and interests of a customer with a product or service they offer provides a value to the recipient, whereas the con has no intention of providing anything of value to the recipient.

Social engineering often leverages one or more of the following tactics:

- Pretexting

- Impersonation

- Psychological Pressure

- Social Proof

- Reciprocity

- Foot-in-the-Door Technique

- Baiting

- Quid Pro Quo

- Cognitive Overload or Distraction

- Appeal to Authority

These tactics are leveraged by appeals to:

- Authority

- Urgency

- Trust

- Scarcity

- Reciprocity

- Rapport

- Social Consensus

- Fear

In advertising, it’s not unexpected to have a call to action prompted by a variety of these:

Urgency and Scarcity:

“Limited time offer while supplies last, order now.”

Reciprocity:

“Order now, and we’ll send you this free gift.”

Trust and Rapport:

“The brand you know and love.”

In advertising, these prompts are transparent and a product or service is legitimate. We’ll prompt our exploration of these suspect video ads with investigation into a method never used in legitimate advertising: Impersonation.

Deepfakes are impersonation by definition.

An Examination

I wanted to start examining these videos first by estimating the likelihood that a person would mistake the video for the actual person portrayed. That is, how authentic the Deepfake appears. There are tools to detect deepfake videos, but deepfake detection is not the purpose of this analysis. Given the subjects of the videos, the purpose of this analysis is determining the impersonation value, which is to say, how likely a person would be to identify the deepfake portrayal as the subject intended.

I found two ads that obviously depicted well known figures that I have used for this test:

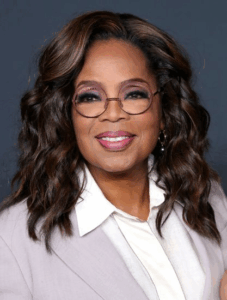

One video depicts a likeness of Oprah Winfrey and the other depicts a likeness of Robert Fitzgerald Kennedy Jr.

(insert image TRUE oprah) (insert image DEEPFAKE oprah)

For visual representation, I used the python library face_recognize (https://github.com/ageitgey/face_recognition) to do facial recognition comparisons. With this library, the tolerance ranges are set with a parameter variable “tolerance” which is default set to 0.6 with lower values representing a stricter condition for a positive match. Anything below 0.4 is considered ‘strict’ with anything between 0.45 and 0.6 being considered ‘balanced’ resulting in a likelihood of a matching facial pattern.

Bare in mind that each of these are small samples, not indicative of large scale statistical analysis, but serves adequately in our case.

In order to get started, I collected several sample images of the genuine subjects and initially compared the known true images to each other. In this case, knowing that the images provided genuinely are the subject, we might expect a 100% match rate, but that’s not the case.

The numbers for each sample are as follows:

Oprah Samples TRUE images:

Total Positives: 26

Total Negatives: 10

For 72.22222222222221% positive match.

At tolerance 0.49

RFK Jr. TRUE images compare:

Total Positives: 45

Total Negatives: 4

For 91.83673469387756% positive match.

At tolerance 0.49

As we can see, the sample images of Oprah had far more variation. The varying styles of lighting, angles, and different glasses frames over time created a different facial recognition profile. The main portrait image from Wikipedia for Oprah, for instance, has thick, dark glasses frames unlike any other picture in the sample and produced zero matches to any other facial photo of Oprah. Likewise, the RFK Jr. photos overwhelming verified each other given the common stoic expression in his photographs with ‘straight on’ photography. The majority of negatives from the RFK Jr. set were a photograph taken from Wikipedia of him at the IronMan marathon, with different lighting, a more elevated focal point, and the subject is smiling. I also can’t discount any training bias the facial_recognition library may have in regards to identifying male/female or different race subjects with more or less precision, which has historically favored Caucasian male subjects.

These numbers provided the baseline for comparison between media samples. With this, we can assume that the average user may, for instance, look at one or two of the images from the sample of genuine subject photos and question if that subject photo is a genuine representation of the subject (particularly in today’s AI generated content world), but the vast majority will be recognizable.

Then, I ran each of the genuine sample pictures against a series of screenshots from the respective ads and got the following results:

Oprah Comp with TRUE samples to DEEPFAKE screenshots:

Total Positives: 25

Total Negatives: 17

For 59.523809523809526% positive match.

At tolerance 0.49

RFK Jr. comp with TRUE samples to DEEPFAKE screenshots:

Total Positives: 61

Total Negatives: 30

For 67.03296703296702% positive match.

At tolerance 0.49

While there is a decline in the percentage match between all of the deepfake stills and the selection of genuine pictures, it is still overwhelmingly positive. In the case of Oprah’s Deepfake sample the decrease in likelihood from the original baseline is ~12.7% and when we consider that the original likelihood was only ~72.2%, meaning that our original confidence deficit was ~27.8%, we can conclude that it wouldn’t be much of a strain to imagine the average person being deceived by this particular video based on visual representation. And while the RFK Jr. matching to the deepfakes is nowhere near 91% it’s still over 65% with our moderately strict tolerance levels. It’s reasonable to conclude that the average individual would be able to identify the deepfake video subject as the intended individual based on these statistics. It’s also reasonable to conclude that these are quickly produced videos where a ‘good enough’ quality is the intent of the creator.

As an amusing side note:

I recently asked ChatGPT Sora to create an image of a character described in my second novel. I used that first image to ‘remix’, and specify to Sora that I wanted to create different images describing different situations in the book using this character as our model. Doing facial_recognition comparisons of the more than two dozen images created by Sora, there was only a ~25% match rate between all the images using facial_recognition at a tolerance of .50. My point in mentioning this is that generative AI using it’s own baseline creation to generate more ‘like’ content is still below the threshold of our variance from real and deepfake images, and that with all of the variation in Oprah’s style and look, there is still more than double the rate of positive recognition with facial_recognition than there are for sample images of purely AI generated models.

The purpose of a deepfake is to be convincing, and AI generated portrayals of others are trained from genuine source material of the subject, so it shouldn’t be surprising to anyone that the faces of the individuals portrayed match the known faces of the subject. It is also interesting to note that models creating deepfakes from known subjects are, at least from the implication of the Sora test, more consistently recognizable from a known subject than a novel, AI generated model.

Unfortunately, I quickly recorded these videos with the built in Ubuntu screen recorder, which doesn’t support audio recording, so I’m unable to play back the audio for dialog or voice comparison, but, for record, the python library ‘resemblyzer’ allows one to do a similarity comparison of voice patters in a similar fashion to how we would use face_recognition for comparison. You’ll just have to take my word for it that RFK Jr.’s trembling, raspy voice was pretty well reproduced in the deepfake.

It’s not difficult for individuals to make deepfake videos with online tools. A convincing, quality deepfake can be made with 10 minutes of footage, but as little as 15 seconds of footage is sometimes all that’s needed, as advertised by popular deepfake/lipsync service website kapwing.com.

Interestingly, the kapwing website has a few FAQ, which I thought to share here:

Can deepfake content be detected and how can you tell?

It is extremely difficult for the average social media user to detect deepfake content — just 17% of people have completed Kapwing’s AI Quiz which requires answering whether celebrity speeches are real or fake. Some of the most obvious giveaways are out-of-sync speech, inconsistent background details, unusual limb or face movements, video glitches, and blurring. Researchers, tech companies, and video experts use frame-by-frame analysis alongside deepfake detection software to help identify deepfake content and keep the internet a safe space. You can also flag harmful deepfake content with the app or website it appears on.

I’m not sure if they mean “17% of our users,” but it’s not surprising to me that users of a deepfaking platform are disinterested in taking surveys for identifying deepfakes. This quote also omits mentioning the conclusion of said survey, which would be supremely relevant for the discussion at hand.

And interestingly, according to their FAQ:

“`

Can you re-create celebrities using AI?

No, you cannot use Kapwing’s AI Image Generator to create replica images of celebrities. This is due to two key considerations:

Right of publicity: Celebrities have a “right of publicity,” which protects their name, image, and likeness from being used for commercial purposes without their consent

Copyright: If AI-generated images are based on existing copyrighted photos or artwork, this could infringe on the copyright of the original creators“`

So, Kapwing, at least, states the legal reason not to copy likenesses of celebrities, and their terms of service include terms that prohibit such content creation. As always, however, we should expect that end users may not respect these terms and Kapwing is far from the only online service to offer these services online, and obviously, self hosted methods exist.

Additionally, the videos in question do not directly advertise a product or service, but, instead, provide a baiting scheme that finally encourages a user to follow link.

I don’t have the original dialog from these videos to see if we can find further hints about ‘Oprah’s’ secret pink salt weight loss recipe or ‘RFK Jr.’s’ diabetes reversal cure ‘they’ don’t want you to know about, but we can explore the common syntax of baiting in online advertisements that we’re commonly seeing today.

Baiting is a tactic used in social engineering to appeal to a sense of temptation or curiosity.

An all too common line anymore in these AI generated ads goes something like:

“They hate it when you do this, but they can’t stop you. Click here to learn more.”

the Syntax of this social engineering ploy reads much like

$DislikedAuthority $verb(NegativeEmotion) when you do $(UnspecifiedAction=”this”), but $Validation. $CalltoAction.

It’s a great mad lib.

Since we’re already on the subject of AI usage in technology, I thought I’d include some outside influence.

I asked Grok to supply me with a few pieces of input:

Randomly name a generic commonly disliked authority figure organization.

OmniCorp Regulatory Board

Randomly name a negative emotion.

Despair

(Maybe I’m fooled by the language models, but I don’t think Grok ‘randomly’ picked the villains from RoboCop)

and after getting a couple of suggestions from Grok, I needed a light-hearted happy ending, so I did the human thing and made up a jovial happy ending, myself:

The OmniCorp Regulatory Board despairs when you do this, but it’s not past your bedtime. Click here to learn more.

The BAIT in this statement is the word ‘this’ which is an unspecified pronoun. In order to learn what ‘this’ is, the user must click the link, and only then will their curiosity be satisfied, likely when they land on a page that has nothing to do with the previous advertisement.

But why is this particular appeal to personality so popular? I’m no psychologist or expert on human behavior, but understanding the concepts of social engineering, I think we can dissect this quite easily:

This appeal is targeted for individuals who are disruptive personalities: people who are either openly rebellious or silently harbor resentment.

Invoking a disliked authority figure creates an appeal to emotion. In this case, the appeal to emotion is anger. When we experience anger we become emotionally incapable of empathy and the quality of our judgment is reduced.

If the appeal to anger is successful, the suggestion of the disliked authority figure experiencing a negative emotional state will produce a positive emotional response in favor of the message, increasing trust, increasing the receptiveness of the recipient. This is instant rapport.

Next, the messenger provides a ‘false solution.’ This is never actually explained in the pitch. This is provided as a ‘simplicity’: “this one thing,” “This easy recipe”,”this one simple trick.” This is where the actual sales pitch is happening. This is where the call to action, the baiting, is originating.

The final validation of “they can’t stop you” or “but it’s not illegal” is an empowering statement for the rebound. This kind of statement is a way of making the recipient of the message feel like there are no consequences for action. This further compels the motivation for the call to action.

And finally the call to action: “Click here to learn more.”

Now, admittedly, I’m not interested in following all of the ‘click here’ advertisements I see. I can’t assure you that there is a Cross Site Scripting request on the other end of that click or a sloppy, repackaged browser exploit, but I’m pretty certain that Oprah Winfrey’s magic pink salt weight loss solution or RFK Jr.’s Apple Cider Vinegar Diabetes cure is not. If the ad in question is willing to employ the fore-mentioned tactics involving impersonation and deception it stands to reason that there’s nothing legitimate on the other end.

Now, let’s consider the psychology of the person motivated by this process and why they are the ideal mark for a scammer.

A disruptive personality is likely to reject authority and take risks. They are more likely to react than to analyze. This means that the ‘conversion’ of the call to action is more likely to be successful, but also that in the event that the call to action is a con, they are less likely to report a scam to the authorities. In other words, an ideal ‘mark’ for a scammer.

In these kinds of ads we see an impersonation with an appeal to authority based on individuals of position, experience, and wealth. We see appeals to urgency: “Click the link before they take this video down.” We see appeals to simplicity: “With this one simple trick.” We see social proof and social consensus: “All my friends are jealous of how much weight I lost since.” And we always see baiting motivating a call to action. As mentioned earlier, we see many of these same tactics in advertising.

Identifying and Avoiding Social Engineering in Ads

One of the simplest ways to avoid social engineering in advertisement is to simply use an ad blocker. If you don’t see the ad, you’re not likely to fall prey to it. But, that doesn’t always work for every situation. Sometimes you need to allow or whitelist ads to receive a web service. Sometime’s you’re not in control of the computer you are using.

Simply put, as technology advances and digital impersonation improves, it is going to become impossible to distinguish artificially generated impersonation videos from the legitimate individual portrayed. Any ‘tips’ or ‘tricks’ to look for right now, like hands, mouth synchronization, expressions, breathing, etc. are all constrained by the current technical limitations that are going to be accounted for and perfected. Today’s ‘tells’ of an AI generated video are already in the devnotes #TODO list. We can not depend on observations of technical failures in generated content as a means of identifying generative AI impersonations. Instead, we need to focus on the traditional means of identifying social engineering and do our best.

Trust No Solicitations

Who initiated the conversation? If it wasn’t you, don’t implicitly trust it.

Scenario:

You receive a phone call from ‘Brad at your Internet Service Provider’ who “Needs to talk to you” “about your billing information.”

What do you do?

You hang up the phone and call the 1-800 number on your ISP’s billing statement and asked to be transferred to billing, and inquire if there are any issues with your account. When they tell you ‘no,’ you know ‘Brad’ was bad.

Advertisements, by definition, are solicitations.

Know who you’re talking (or listening) to.

Anymore, in digital communications this is difficult. Real time deepfakes have made video calls just as suspect as any other digital video.

https://www.cnbc.com/2025/07/11/how-deepfake-ai-job-applicants-are-stealing-remote-work.html

https://indeedinc.my.site.com/employerSupport1/s/article/How-to-spot-a-deepfake-during-a-video-interview?language=en_US

As this increases, I’d encourage people to use PKI, PGP keys, and have key signing parties to establish their own trust networks, but first and foremost, be skeptical of all digital communication formats.

In security, we define the process of gaining access as a flow:

Identify > Authenticate > Authorize > Access

This goes back to the scenario with Bad Brad:

Use ‘known good’ communication routes (ie the 1-800 number) to Authenticate the Identity of parties with which you communicate.

Ask yourself, “What does this person want me to DO?”

Most people engaged in conversation want something. If you can identify that, you can likely determine motivations. In a legitimate advertisement, the motivation is transparent and always “Buy This.” If what the ad is selling isn’t obvious, it’s not an advertisement.

Slow Down.

Appeals to Emotion and Urgency are about convincing a person to surrender their judgment and agency in favor of taking actions that produce the attacker’s desired outcome. Question urgency. Ask how this message makes you feel.

Is the message you’re receiving rushed? Does it make you feel frustrated, angry, sad? Do you feel like you want to help somebody you don’t know based on the story alone? Then ask if there is some appeal to emotion at play. Do you, and you alone, need to take action RIGHT NOW? Then, that is an appeal to urgency.

Ask yourself, “What’s the worst that could happen?” – AND ANSWER IT.

During the COVID19 pandemic, President Donald Trump, at one point, suggested on live television that people take disinfectants internally and suggested that people try other unconventional treatments. He asked, “What’s the worst that could happen?” The surgeon general, hastily stepped towards the podium and succinctly answered, uttering the words, “You could die.”

Understand the ramifications of actions you take based on outside influence, and escalate the conclusion to the worst possible outcome before considering taking action.

Ask if the worst possible outcome is in your best interest.

It almost never is.

Ask for another opinion.

The collective judgment of a larger group of people tends to be harder to manipulate for most social engineering attacks with propaganda being the obvious exclusion. Including multiple individuals in the judgment process makes exploitation far more difficult and it takes time to include more people.

I’d like to close mentioning that within a couple of weeks the video ads mentioned in this post were no longer in circulation, so it would seem that someone considered celebrity likeness and took action. But, in less than a month I found myself hearing the exact same robotic toned speech about the magic pink salt recipe from a generic looking, apron clad lady. We shouldn’t expect this sort of thing to go away.

This article highlights several key CompTIA Security+ and Pentest+ objectives, including social engineering techniques, psychological attack vectors, impersonation threats, and mitigation strategies relevant to modern cybersecurity professionals. By examining deepfake use in unsolicited media, we illustrate how emerging technologies expand traditional threat surfaces.